At a time when interest rate hikes to battle inflation are grabbing the headlines, another of the Bank of England’s monetary policy tools — quantitative easing, or QE for short — has also been in the news.

The Bank’s long-running QE programme, aimed at supporting the economy via massive bond purchases, is being reversed by selling bonds back to the financial markets.

Here we recap the basics of QE, why it’s now being reversed, and what this could mean for investors.

What is QE?

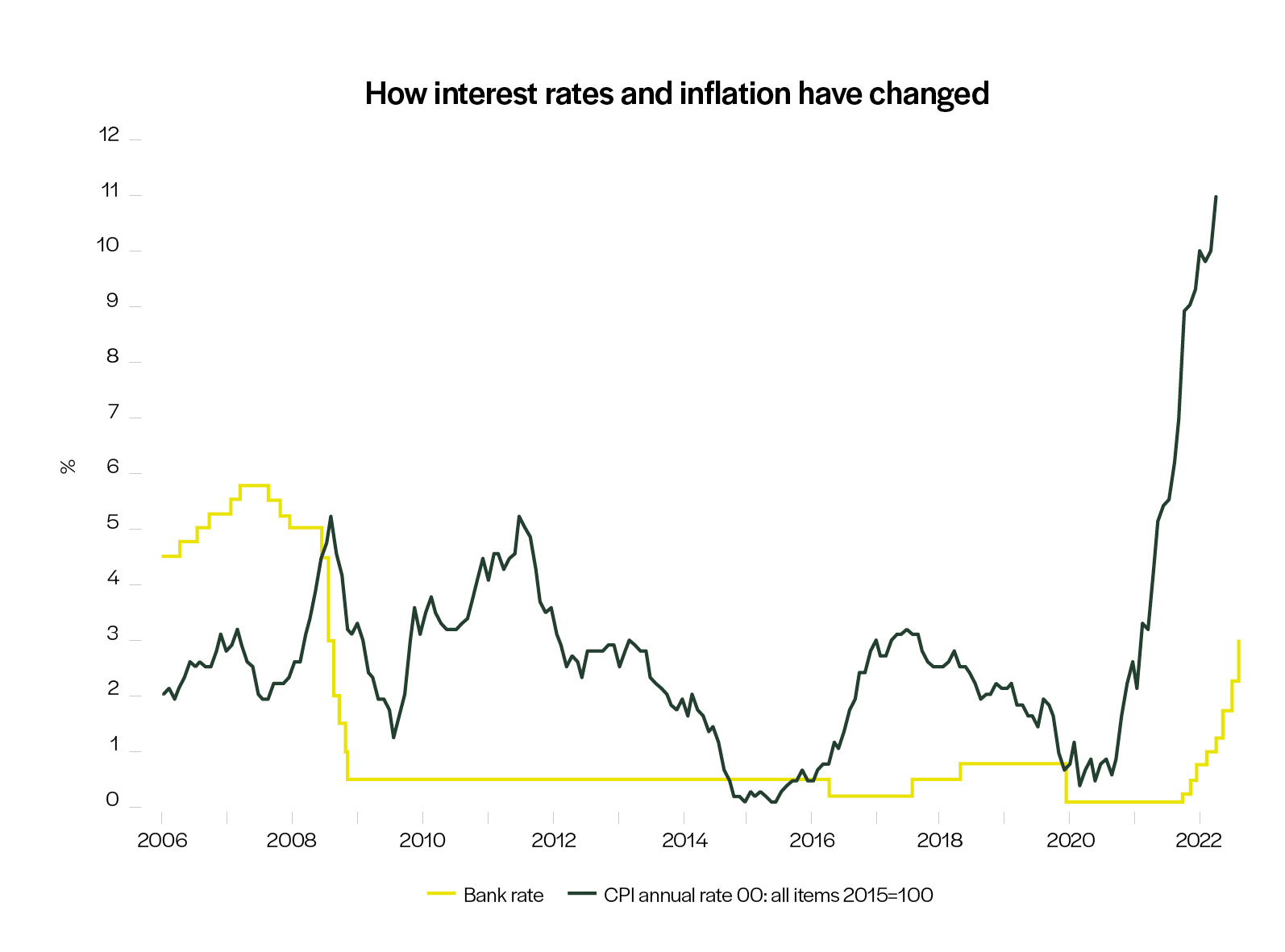

While the focus now is on how high interest rates may need to rise to beat soaring inflation, it’s easy to forget that only a year ago the UK base rate was just 0.1%. Rates had also been below 1% since the 2008/9 financial crisis.

Source: Bank of England and Office of National Statistics

The aim of those very low rates was to stimulate the economy and keep inflation from undershooting the Bank’s 2% target for price rises.

But such reduced rates also left minimal scope for further supportive cuts after the financial crisis and during subsequent shocks from Brexit and the pandemic.

The Bank therefore adopted QE as an additional way to help lower borrowing costs and boost spending in the economy.

Here’s what QE involves. The Bank buys up government bonds (known as Gilts) from existing holders such as investment funds and financial companies. These purchases are paid for with money newly created for the purpose — which is why QE is sometimes described as ‘money printing’ (even though the created cash is electronic rather than physical).

This increased demand for Gilts pushes their price up, which lowers their yield (effectively the bond’s interest rate).

This in turn lowers the interest rates on savings and loans, which encourages consumers to spend and businesses to invest.

Other central banks, especially the Federal Reserve in the US and European Central Bank (ECB), adopted similar QE policies to support their economies.

And the scale of such purchases has been extraordinary. In the UK, the Bank has bought up a total of more than £800bn of gilts — a third of the government bonds in issue — including £450bn during the Covid pandemic alone. Meanwhile, QE purchases by the Fed and the ECB have been in the trillions.

.jpg)

Source: Bank of England

Why is QE being reversed?

The return of high inflation means that instead of trying to stimulate their economies, central banks are now looking to slow them down to help control rising prices.

Primarily this is done by raising interest rates, but also by unwinding QE through “reverse QE” or “quantitative tightening” (QT for short).

In practice this means reducing their accumulated stock of bonds by selling them back to the market, or waiting for bonds to reach the end of their term and not reinvesting the proceeds.

In November the Bank of England became the first major central bank to start selling by offloading an initial tranche of £750m Gilts, and says it plans to reduce its overall stock of bonds by £80bn over the coming year.

What could the changes to QE mean for investors?

Many investors will have benefited from QE: bond prices rose, while lower bond yields helped push up the value of other assets like shares and property.

But with QE having boosted bond prices, inevitably there may be concerns that switching to QT could now put downwards pressure on prices.

The Bank of England’s approach so far to unwinding QE has offered some reassurance for investors. Its first sale of £750m bonds saw what the Financial Times described as “healthy demand”, with more than £2.4bn of bids from buyers.

And the Bank has said it will be proceeding gradually and flexibly, taking into account changes in market conditions. This included postponing its initial bond sale from earlier in the autumn to avoid the bond market turmoil following the mini-Budget of Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng.

QT is likely to remain a backdrop to markets for some years. However, with central banks having made widespread use of QE over the past decade or so, investors should not be surprised if this large-scale bond-buying is employed again at some point in a future economic cycle.