We’re in the early stages of recession, and expectations are starting to come down. But a more subdued stock market is actually a good sign.

It’s been an interesting year for equities, largely defined by the transition from post-Covid prosperity to exorbitant inflation and recessionary conditions the world over. The first half of 2022 featured continuous good news on the earnings front as businesses benefited from the tailwinds of rising prices. Interest rates were still low, and people had a bit of money to spend, which enabled profits to stay robust. As summer progressed, expectations started to drift down as market participants realised things were about to get harder—the evidence of an impending economic slowdown became more difficult to deny, and interest rates began to rise in earnest. Valuations retreated as people worried about the effects a recession would have on their equity investments.

The ups and downs of valuations

Let’s take a quick trip down memory lane and look at how valuations rocketed in the euphoric days of the young internet. In the late 1990s, valuations climbed as investors became enamoured with the ‘new economy’ and the promise of prosperity untold enabled by the tech boom. They got carried away; they overpaid, and eventually, that had to be unwound. It did so via the protracted bear market (a rare occurrence in which the stock market falls by 20%) of 2000-2003.

Eventually, of course, the economy started to recover, stimulated by arguably reckless monetary policy. We witnessed a housing boom as more people were deemed eligible to buy homes. This, as we all know, led to the subprime mortgage crisis that ballooned into the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-08. One aspect of why this happened is because companies were earning above and beyond their true earnings power (making their valuations too high), which wasn’t sustainable in the long term.

Learning from our past

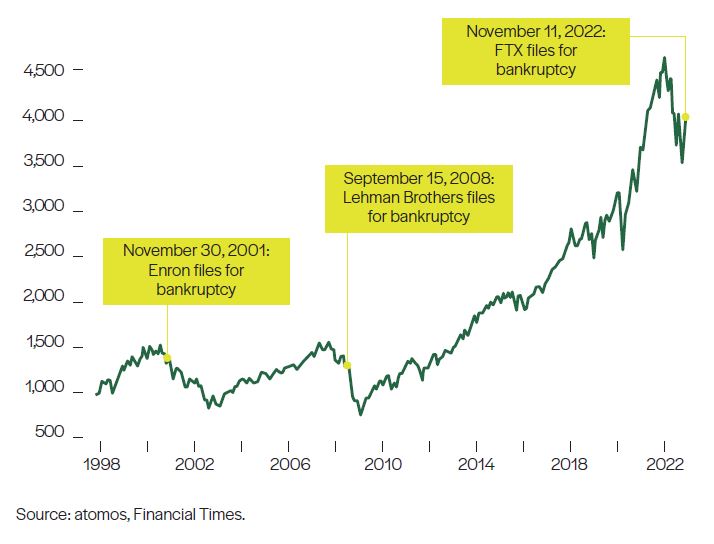

Here’s the important thing to note: these sensational falls from grace tend to happen halfway through a market correction. Mid-November witnessed the bankruptcy of FTX, very recently considered a leader in the cryptocurrency space. The 2000s saw Enron executives carted off in cuffs. (Keep reading for more on these corporate catastrophes.) This, as evidenced in the chart below, provides us with a yardstick by which to measure how far along this market correction we are.

Chart 1: Valuations tend to rise before the economy stumbles

Think of the economy and the stock market as two separate players: while the economic recession may only be a third of the way through, we’re probably already halfway through the (temporary, it’s important to note) damage to the stock market.

Looking at these past scenarios is helpful because it allows us to start formulating a plan. Understanding the potential dips from where we are now puts us in a good position because we can start to factor in potential price falls (and keep calm amid a flurry of nerve-wracking news stories). Valuations dropping provides an opportunity to start considering how you’d like to reintroduce risk to your portfolio.

As for economic growth, we had two negative quarters in the US followed by a positive GDP reading. Inflation seems to be falling from its peak, but in the style of a feather as opposed to a brick. So are the waters safe for swimming? Not quite yet, but ready yourselves. We’ll see some volatility ahead, but the market tends to turn when the economy is at its worst. Put another way, the market recovers before the economy does . . . and as such, we might just be better off than it seems.

Investment View: Why the implosion of FTX bodes well for the global economy

Our still-young century has witnessed a number of sensational—and criminal—financial scandals. That they all happened at a similar point in the business cycle is no coincidence.

A brief overview of what happened last month: Crypto kid Sam Bankman-Fried, a relatively recent MIT graduate and major donor of US President Joe Biden, opened his cryptocurrency exchange in 2017 after making millions from buying Bitcoin in the US and selling it at a premium in Japan, where prices tend to be higher. At the same time, he founded a cryptocurrency research and trading firm called Alameda Research, of which he appointed his classmate and on-again-off-again girlfriend CEO. To make a long story extremely short, Alameda, as an independent company, lost a lot of money as crypto fell earlier this year. Rather than allowing Alameda to fail (which would have created reputational damage and possibly put FTX out of business earlier, as Alameda owned billions in the former’s in-house tokens, called FTT), FTX bailed its sister company out. Investors in FTX, spooked by the news surrounding not only FTX but the unravelling of the crypto ecosystem as a whole, rushed to get their money out—only to find the coffers had been drained. $8 billion worth of client cash was gone, very likely lent to the doomed Alameda.

The story bears a disgraceful resemblance to a notorious corporate collapse in 2001, at the dawn of online trading. Enron, a utility company that made billions trading energy derivatives—at least on paper—experienced a dramatic downfall when it was revealed that the company had been doctoring its books, fraudulently inflating the company’s revenues and hiding massive losses in its special-purpose subsidiaries. Investors in the crooked company lost $74 billion over four years. The scandal necessitated notable changes to the financial industry, including the passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which criminalised this kind of fraud. Enron’s bigwigs were sentenced to years in prison. Credit ratings agencies and the Securities and Exchange Commission were berated for their lack of oversight.

If you want to know where you’re going, look at where you’ve been

Given its somewhat sci-fi feel, there are many who would say this year’s crypto collapse isn’t all that surprising. But the intangibility of it all actually has little to do with the economic importance behind the high-profile bankruptcy of FTX. Rather, the critical component is timing. As we’ve previously mentioned, the market tends to turn earlier on in the business cycle than most people would assume. And a corporate collapse of this magnitude is nothing if not a reckoning.

While the contagion effect of FTX’s end has thus far been mercifully limited, the company’s demise follows a pattern we’ve seen throughout the 21st century. In times of good fortune, people are emboldened. That feeling can lead to reckless investing akin to gambling. The chart below illustrates this flow:

Chart 2 - High profile bankruptcies generally precede market recoveries

In the Enron era of tech-bubble excitement, valuations were well up. At one point pre-implosion, the company was trading at seventy times its price-to-earnings ratio. Its stock price increased by 56% in 1999, and by 87% the next year. The initial stock market weakness and tighter credit conditions triggered the collapse, which provided an important signpost to investors that speculation and excess were being purged from the system. This left the market poised to resume its upwards march. And that it did, helped by low interest rates, until history repeated itself with the fall of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers midway through the GFC.

And therein lies the lesson to take from the failure of FTX: if we’re using history as a guide, timing is on our side. Newsworthy ruin often represents a turning point. Earlier this year, financial assets were kept afloat by a wave of liquidity and stimulus. Yes, we’re in for a recessionary winter. But valuations falling allows for fresh growth in the new year. From a market perspective, we’re halfway through the pain.

The information and opinion contained in this Monthly Commentary should not be treated as a forecast, research or advice to buy or sell any particular investment or to adopt any investment strategy. Any views expressed are based on information received from a variety of sources which we believe to be reliable, but are not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness by atomos. Any expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. Investing involves risk and the value of investments, and the income from them, may fall as well as rise and is not guaranteed. Investors may not get back the original amount invested.