The legacy of ‘22 means a muted start to ‘23

The extraordinary year we’ve left behind has rendered 2023 a pivotal period for global economies.

After the profusion of pies we consumed last month, we’re in no mood to mince words: 2022 was a difficult year, and we’re in for a continuation of challenging times as central banks and international governments seek to right their economies. To put it in perspective, equities and bonds alike ended 2022 down more than 10%. It was a year largely devoid of safe havens, aside from perhaps the US dollar, which is quite an unusual landscape.

“Central banks are in reactive mode—which is a polite way of saying they’re making it up as they go along.”

Haig Bathgate, Head of Investments

So, how did we get here? Inflation seems the obvious answer, but that doesn’t quite cover it. Rather, markets have been influenced by the large-scale reaction to inflation—by what central banks have seen fit to do about it. The US and UK began raising interest rates right at the turn of last year. The European Central Bank was late to the party but snuck in a rate rise as 2022 wound down. The emerging world underwent collective monetary tightening as well, representing somewhat of a concerted effort in the fight against inflation.

The good, the bad, and the sticky

Interest rates and inflation are high. Unemployment is low. Valuations are evening out, but earnings projections are still precariously lofty. This is a combination that is unlikely to last.

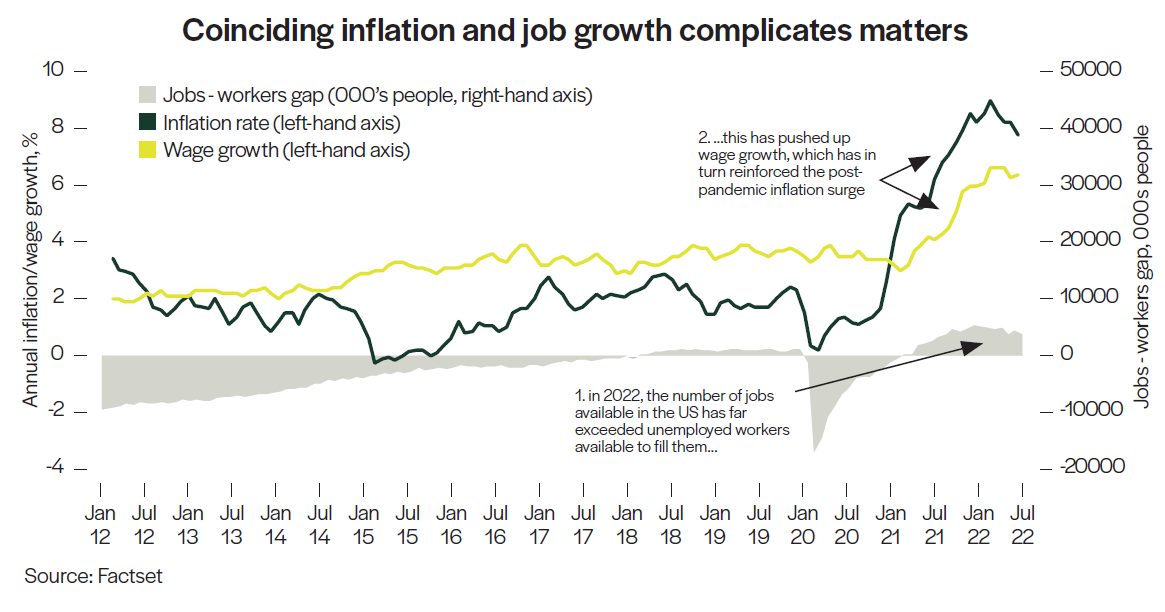

6.5% - October’s recordlow unemployment in the eurozone, which, antithetically, complicates the fight against inflation. (Source: Trading Economics)

Let’s break it down: the monetary tightening we’ve seen so far has hovered around ‘just right’. It’s been sufficient to hamper growth but has not caused a recession in the US (yet). In stock markets, valuations are starting to readjust to more appropriate levels for the pervading economic climate, but earnings expectations haven’t materially declined. This suggests that the scale of monetary tightening hasn’t been fully digested by markets, which means they may be in for more pain. Inflation is sticky, still languishing near or at double digits—but wages aren’t budging either. Wage growth sounds like a good thing for individual households, but collectively it presents a challenge, as it allows inflation costs (higher prices) to be more readily absorbed by the public, which keeps consumer prices up.

Where we’ve been vs. where we’re going

To stick with the meteorological metaphor, we are probably at a midpoint—the eye of the hurricane, if you will, and we have the other side of the storm to endure. While we struggle to hold the opinion that next year will guarantee strong returns after the declines we’ve seen in ’22, inflation is slowly inching down. Central banks are vigilant. From a portfolio perspective, defensive assets appear desirable, as earnings adjustments are yet to come. Retain a long-term mindset as the year disappears and a new, if familiar, day dawns.

Investment view: Five things to watch in the next 12 months

We’ve moved beyond resolutions and predictions to tell you where your focus should lie as

you navigate the new year. Here’s what to look out for from January onwards.

1. Inflation will fall—from the headlines

While still very much a series regular, inflation is unlikely to be the star economic stat as the plot unfolds in the new year. This is because—encouragingly—there’s building evidence that the rate at which consumer prices are rising is beginning to peak, and even slow in the US. Rather, the data likely to be foremost in central bankers’ minds concerns growth, which is expected to stall across the world. Given the hawkishness of central banks in the latter half of ’22, it’s not clear how negative the growth environment will become in response to ongoing tightening measures (interest-rate rises, or, in the case of the Bank of England, Federal Reserve in the US and soon the European Central Bank, the selling of financial assets). To be clear, inflation remains fundamentally too high. The result of this is a deterioration in the growth environment because central bankers have been so vigorously fighting the inflation fight.

2. We’re all in this together

Geopolitics are set to play an even more meaningful role as the world enters a recessionary period, and as such, we need to start thinking more directly about their influence. The rise of China as a real competitor of the US; the war in Ukraine and its implications on Europe; continuing strife in the Middle East; and Britain’s divorce from the EU lend an air of unpredictability to investing, and one that markets have traditionally struggled to cope with. But the very nature of this instability means we don’t know what the outcome will be, and it’s not impossible that the product will be positive. For example, a resolution to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict could mean better fortunes for consumers and economies across Europe: peace could pay dividends. Take a hard look at your geographical exposures and seek diversification; it’s your best defense against unknown – and unknowable – outcomes.

3. A marriage of monetary policy and politics

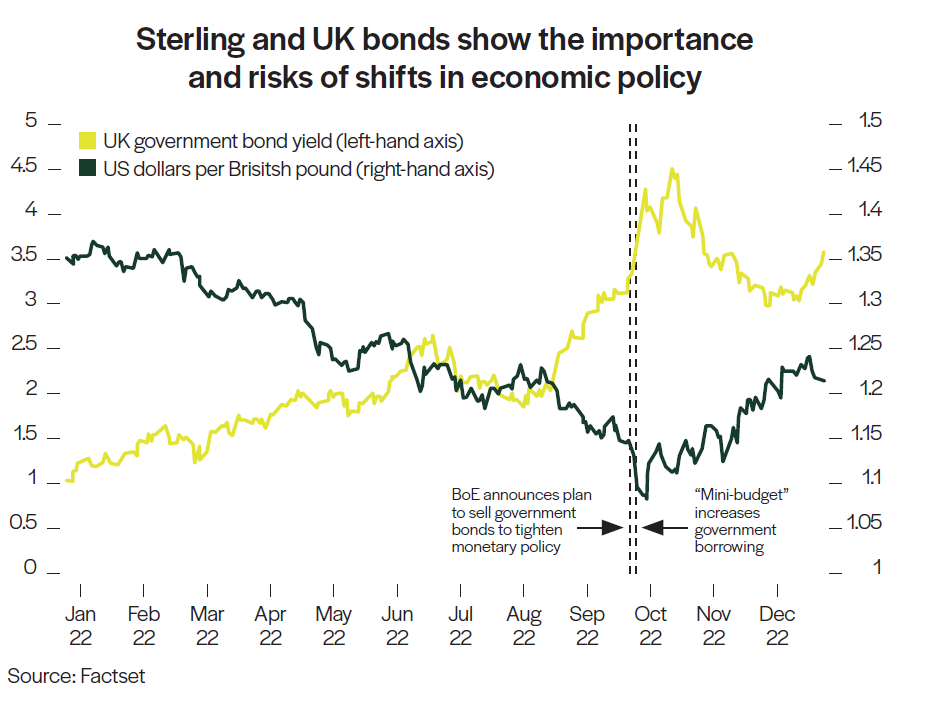

As Britain saw all too clearly in September upon the revelation of ex-Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s doomed mini-budget, the policy challenge central bankers and politicians jointly face is acutely difficult right now. The UK is under particular pressure given relatively higher inflation than the rest of the developed world and a fragile currency. The interplay between the government and monetary policymakers (the Bank of England, or BoE) will have a marked influence on UK-focused assets like housing prices, small-cap equities (which include domestic businesses) and sterling. If the BoE needs to keep raising rates, the government will be faced with the difficult question of whether or not to stimulate the economy (through higher government spending or tax cuts), and the extent to which UK government bond markets and sterling will tolerate the higher borrowing required. A delicate balance would be needed to ensure such measures wouldn’t bump inflation or spook markets yet again.

4. TINA, meet TARA

In an era of low growth and low interest rates, TINA reigned supreme. The acronym, which stands for ‘There is no alternative’ refers to the appeal of equities and other riskier assets as the only avenue by which decent returns could hope to be made. Higher interest rates and some corporate shocks (such the decline of cryptocurrency and November’s FTX bankruptcy) are suggesting to market participants that ‘there’s a real alternative’ (TARA) now in the form of higher-yielding assets such as bonds. As market focus switches from inflation to growth, earnings are what to watch. Disappointing earnings will in turn drive down expectations for quarters to come. Keep a close eye on market sentiment.

5. Private property

To a degree, publicly listed asset classes like equities and government bonds have responded to rising interest rates, higher inflation, and declining world growth. But privately held assets have been slow to react. Property is a perennially popular and often rewarding asset. Commercial real estate, in conjunction with equities, is often the keystone of a portfolio. Property prices are starting to move, to varying degrees and in different directions: house prices are falling in response to higher interest rates, while rentals are strong and, in some cases, ascendent.

This will be a year for which to sharpen your critical eye: keep abreast of geopolitical news flow, and ask, ‘Is this a good or a bad thing for markets?’ Look out for signs of weakening growth in economic data releases, and in the world around you; it looks as though things might be most illustrative at home. And as ever, don’t try to time the market—evergreen advice to heed year after year.

In the Enron era of tech-bubble excitement, valuations were well up. At one point pre-implosion, the company was trading at seventy times its price-to-earnings ratio. Its stock price increased by 56% in 1999, and by 87% the next year. The initial stock market weakness and tighter credit conditions triggered the collapse, which provided an important signpost to investors that speculation and excess were being purged from the system.

This left the market poised to resume its upwards march. And that it did, helped by low interest rates, until history repeated itself with the fall of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers midway through the GFC.

And therein lies the lesson to take from the failure of FTX: if we’re using history as a guide, timing is on our side. Newsworthy ruin often represents a turning point. Earlier this year, financial assets were kept afloat by a wave of liquidity and stimulus. Yes, we’re in for a recessionary winter. But valuations falling allows for fresh growth in the new year. From a market perspective, we’re halfway through the pain.